A hoodie-clad dropout from Harvard pitches you on their startup.

They’re on a solo quest to disrupt the world.

They have first mover advantage.

What to do?

Run away

There are many persistent myths about venture investing.

Maybe the most durable is that the next unicorn will be run by another Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates – a brilliant young college dropout on a solo quest to disrupt the world. (Can we please stop saying disrupt?)

That image makes for good theater. It’s also not true. That’s not what unicorn founders actually look like.

- The typical unicorn founder is older. Their average age is 35. If we widen the aperture beyond unicorns and look at the average age at founding for the top 0.1% of fastest-growing new companies – it’s even older: 45. And in that cohort of companies, 50-year-old founders were twice as likely as 30 year old founders to achieve success.

- The founders with the lowest chance of success? They were in their early 20s. The study concluded, “successful entrepreneurs are middle-aged, not young.” (Rock on Morris Chang, who started the “world’s most important company” when he was 55).

- The typical unicorn has multiple founders. In fact, 83% of unicorns had multiple founders – and 100% of the top 10 unicorns did.

- The typical unicorn founder didn’t go to a typical school. Only 20% of unicorn founders went to a top 10 school, and no single school has meaningful “market share” among unicorn founders. Even Stanford is the alma mater of only 5% of unicorn founders.

So the mythical archetype of the fresh-faced Harvard dropout as unicorn founder is just that – mythical.

But the company also has first mover advantage. What about that?

More complicated. But in general, we believe first mover advantage is also a myth – though there is a narrow exception.

The startup world is littered with the skeletons of first movers who were killed by later entrants.

Remember the Pebble smartwatch? No one else does either. They were first mover in smart watches. They burst onto the scene in 2012 after launching what was then the most successful Kickstarter campaign in history, raising $10 million to produce the first smartwatch. In 2015, Apple launched their own. Within a year, Pebble was sold for scrap and ceased production.

Remember the “Crackberry“? They were first mover in smartphones. They once had 85 million subscribers and 50% U.S. market share. By 2017, they were annihilated by the iPhone and were a tenth of that size. By 2022, BlackBerry phones were “decommissioned” — that’s Canada-nice for “your phone is now a paperweight.”

Remember the search wars? Alta Vista? Lycos? Yet Another Hierarchically Organized Oracle? Take a trip down memory lane. All were first movers. All were crushed by late entrant Google.

Remember Netscape? The first internet browser made some people rich. But it got steamrolled by Safari and Explorer. Netscape turned the lights off in 2007.

First movers do get some advantages.

- They have more time than later entrants to accumulate technical knowledge.

- They can preempt later arrivals’ access to scarce assets like talented employees or coveted suppliers.

- They may be able to build an early base of customers who find it inconvenient or costly to switch to competitors later.

- They may have brand advantages, and they may have fatter margins before competition arises.

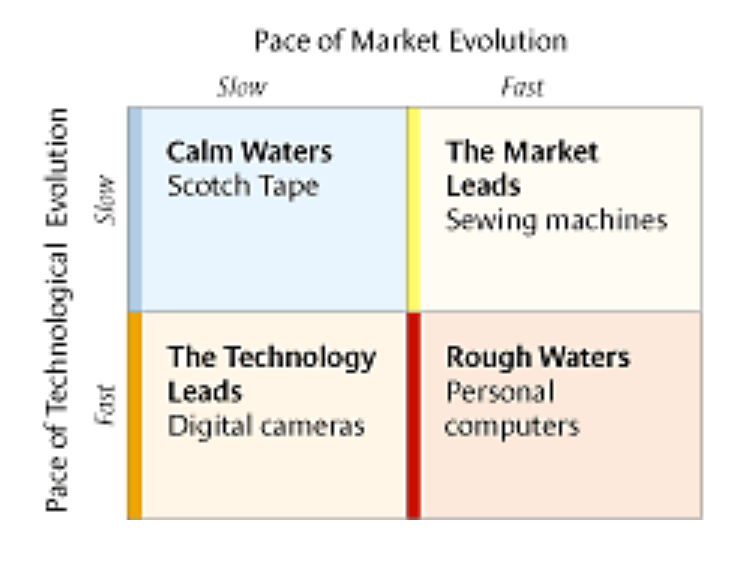

Harvard Business Review analyzed first mover advantage. Because HBR has to put everything into a two by two matrix, they put it into a, you know, two by two matrix. (Does everything need to be a 2×2 matrix?)

The TLDR: the lone set of conditions advantageous to first movers, is slow technological change, and slow market growth.

Think vacuum cleaners. With those conditions, Hoover had no trouble keeping up-to-date technologically and meeting demand, and the gradual pace of technical change made it hard for later entrants to differentiate. That’s why Hoover became a verb.

Across other condition sets, only companies with very deep pockets can enter such a market first, survive in its hostile environment, and withstand a considerable delay before obtaining durable first-mover advantages.

That’s why most conditions aren’t made for startups. And the roughest condition of all is where both technology and market adoption change rapidly. In those sectors – which include many of the largest and sexiest market opportunities, like computers – first movers have zero advantage. That’s why you’re not reading this on a Tandy, Commodore or Kenbak-1.

And that’s why statistically, across all conditions, first-movers have a 47% failure rate, while followers have a failure rate of only 8%.

And that’s no myth.